12

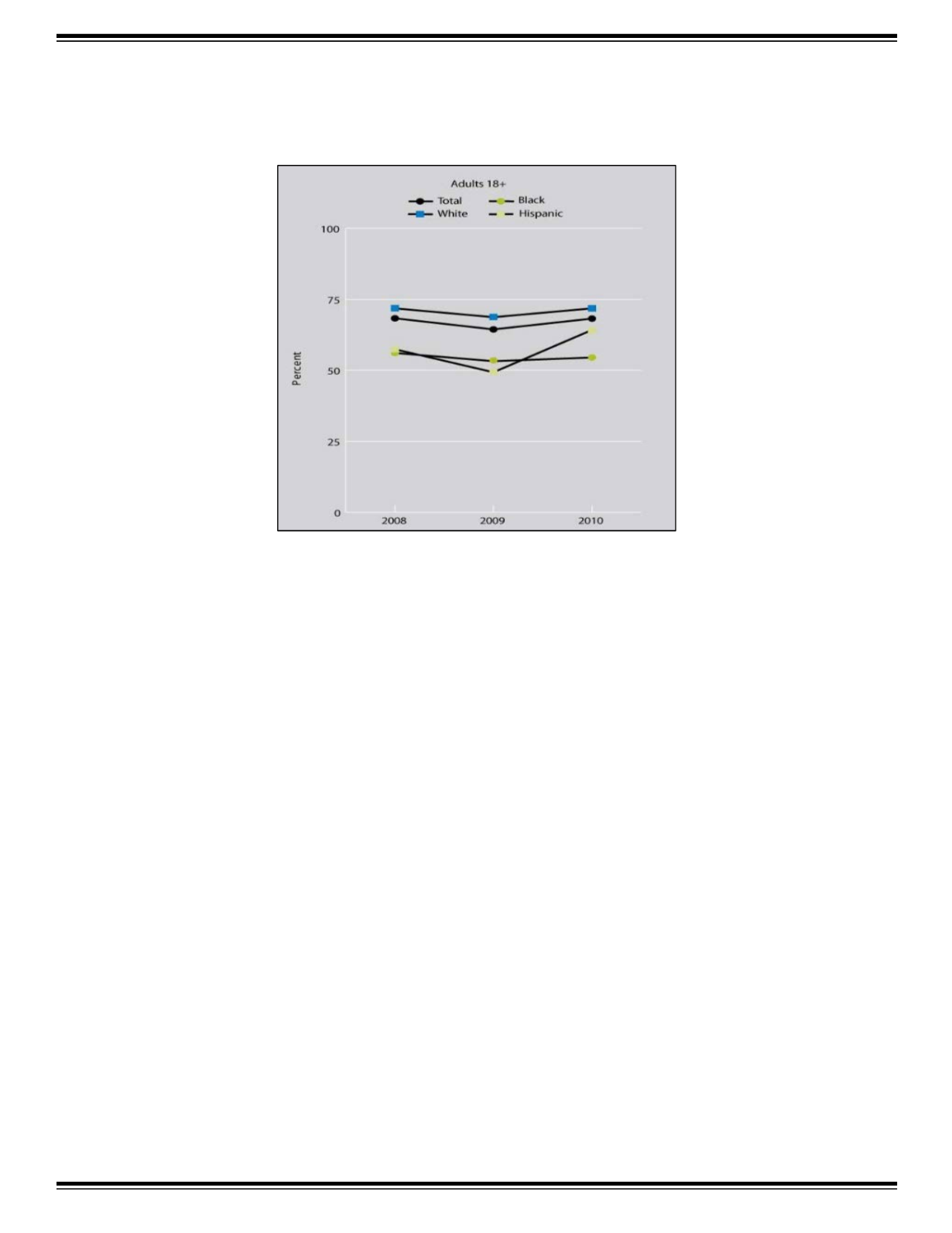

depression, as published in the 2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR). In all years, African American and

Hispanic adults were less likely to receive treatment for depression than Caucasian American adults.

Figure 4: Adults Who Experienced Major Depression and Treatment within the Same Year by Race/Ethnicity,

2008 – 2010

Figure 6: Adults Who Experienced Major Depression and Treatment within the Same Year

by Race/Ethnicity, 2008 – 2010

Source:

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2010.

A 2007 Science Update, by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), referenced a special

issue of

Research in Human Development

, published in the same year that examined then current

trends in prevalence and risk factors for mental health disorders across the lifespan in diverse U.S.

minority populations.

24, 25

Notable findings from the special issue showed that of the more than

2,554 Latinos interviewed for the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), age at time

of immigration was a factor in the mental health of this diverse minority population. According to

Margarita Alegría, PhD.,

et.al., in general, the older the person at immigration, the later the onset of

psychiatric disorders. Those who arrived later in life had lower lifetime prevalence rates than

younger immigrants or U.S. born Latinos. However, after about age 30, the risk of depressive

disorders increased among these later-arriving Latino immigrants, whereas risk tended to decrease

between ages 30-40 for U.S. born Latinos and immigrants arriving before age seven. Latinos

arriving between ages 0-6 had very high risks of onset shortly after immigration, but after several

years, their lifetime prevalence rates approached those of Latinos born in the United States.

25

According to a NIMH-funded analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2011,

older racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to be diagnosed with depression than their

Caucasian counterparts, but are also less likely to get treated once they are diagnosed.

26

Ayse Akincigil Ph.D,

et.al., found that about 6.4% of Caucasian American patients, 4.2% of African

Americans, and 7.2% of Hispanics were diagnosed with depression. Among those diagnosed,

73% of Caucasian Americans received treatment (either with antidepressants, psychotherapy or

both); while 60% of African Americans received treatment and 63.4% of Hispanics received

treatment. These kinds of diagnosis and treatment differences are consistent with previous studies,

the researchers noted. Although they noted pronounced differences in socioeconomic status and

Source:

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2010.

A 2007 Science Update, by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), referenced a special issue of

Research in

Human Development

, published in the same year that examined then current trends in prevalence and risk factors for

mental health disorders across the lifespan in diverse U.S. minority populations.

24, 25

Notable findings from the special issue

showed that of the more than 2,554 Latinos interviewed for the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), age

at time of immigration was a factor in the mental health of this diverse minority population. According to Margarita Alegría,

PhD.,

et.al., in general, the older the person at immigration, the later the onset of psychiatric disorders. Those who arrived

later in life had lower lifetime prevalence rates than youn

ger immigrants or U.S. born Latinos. However, after about age 30,

the risk of depressive disorders increased among these later-arriving Latino immigrants, whereas risk tended to decrease

between ages 30-40 for U.S. born Latinos and immigrants arriving before age seven. Latinos arriving between ages 0-6 had

very high risks of onset shortly after immigration, but after several years, their lifetime prevalence rates approached those of

Latinos born in the United States.

25

According to a NIMH-funded analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2011, older racial and ethnic

minorities are less likely to be diagnosed with depression than their Caucasian counterparts, but are also less likely to get

treated once they are diagnosed.

26

Ayse Akincigil Ph.D,

et.al., found that about 6.4% of Caucasian Am rican patients, 4.2% of African Am rican , and 7.2%

of Hispanics were diagnosed with depression. Among hose diagno ed, 73% of Caucasian Ameri ans received treatment

(either with antidepressants, psychotherapy or both); while 60% of African Americans received treatment and 63.4% of

Hispanics received treatment. The kinds of diagno

sis and treatment differences are consistent with previous studies, the

researchers noted. Although they noted pronounced differences in socioeconomic status and quality of insurance coverage

across ethnicities, these differences did not appear to account for the disparities in diagnosis or treatment rates.

The significance of these findings is consistent with the notion that depression continues to be under-recognized and

undertreated among older minoriti s. According to the researchers, future investigation should explore cultural factors, such

as help-seeking patterns, stigma, and patient attitudes and knowledge about depression as potential aspects contributing to

the disparities.